But there are reasons for Europeans to be hopeful. Technologies that could transform our world for the better are being built in the continent — be it in robotics, nuclear fusion or quantum computers — and today it stands a much better chance of commercialising its scientific excellence.

To avoid repeating past mistakes, and ensure that the next era of innovation can be built to deliver the continent’s first trillion-dollar company, one thing is crucial: Europe needs to celebrate and support experienced founders who are building and investing in the highest-risk, highest-reward ideas.

Secondly, we need to make important changes to reform arcane infrastructure that still holds fast-growing companies back.

It’s urgent that we do.

The tech tree is being built in the West Coast of America. It’s wonderful that it is being built, but the imbalance of where it is being built has a cost and Europe needs to step up, contribute and lead.

The value of repeat founders

The DeepMind story started when co-founders Sir Demis Hassabis and Shane Legg met at the Gatsby Computational Neuroscience Unit at University College London - a unique academic institution where neuroscientists and machine learning researchers come together to collaborate.

Hassabis is many things - a Nobel-winning scientist, a visionary AI researcher - but I believe at least as importantly he was something else: an experienced founder. Twelve years prior to DeepMind, he founded Elixir Studios, a London-based games studio that shut down after seven years.

You can feel the heartache in Hassabis’s quote from a press release as the company wound down: “It seems that today’s games industry no longer has room for small independent developers wanting to work on innovative and original ideas…this was the sole purpose of setting up Elixir and something we could never compromise on.”

Technology start-ups are a relatively new area of the economy and there is still limited understanding of what exactly drives success. A common explanation for why Europe lags the US is excessive regulation, and it is certainly true that founders in Europe face more bureaucratic drag compared to their US peers (I’ll come onto that later).

But I believe it is the role of founders that has the biggest impact. When I think about the hardest-charging founders I know in Germany like Hélène Huby of The Exploration Company or Francesco Sciortino of Proxima Fusion, they blast through regulation and bureaucracy and it is not the core thing holding them back. In particular, repeat entrepreneurs such as Hassabis are a kind of critical keystone species that massively affect the overall health of a continent’s technology ecosystem.

The first and most obvious reason for this is that like any profession, being a tech start-up founder is a kind of craft - and the longer you do it, the more you refine the craft. So when it came time for Hassabis to raise his first round of funding for DeepMind in 2010, he knew better than to waste time on conservative European investors and headed straight to Silicon Valley where he was able to raise investment from experienced founders such as Peter Thiel and Elon Musk.

This is the second reason that experienced founders are so important - for their second or third company they will often tackle harder challenges. Musk is the quintessential example of this - his first company in 1995, Zip2, was an internet city guide, his second in 1999 was an online bank, and his third in 2002 was a space exploration company. What explains this ramp in ambition? I suspect the deepest reason is that having founded a start-up, you know how hard it can be - so if you’re going to try again, you’re even more committed to tackling a mission that is inspiring enough to justify the lows that you know will inevitably come. There’s also a kind of natural selection at play - the harder the mission, the greater the skill level required and the less likely a first-time founder will make it. This is starting to happen in Europe. Alongside Demis and DeepMind, there are examples like BioNTech’s founders Özlem Türeci and Uğur Şahin who previously founded Ganymed Pharmaceuticals in 2001 and Spotify’s Daniel Ek who started Advertigo in 2003.

Audacious capital

As investors, experienced founders are also often a source of the most audacious capital, funding start-ups with a higher level of risk or a longer gestation period before they start to work and make money. The game Civilisation introduced the concept of the “tech tree” - the idea that progress in technology can be visualised as a tree in which new branches of technology sprout from the main trunk and then allow for a network of subsequent branches to grow. For example, semiconductors were needed to enable personal computers.

Experienced founders are often most likely to fund new branches of the tech tree. In Silicon Valley, more than 60 per cent of the partners at top VC funds were previously founders and CEOs; in Europe, by contrast, the figure stands at a dismal 8 per cent.

Things are beginning to move in the right direction. My own fund, Plural, is run 100 per cent by experienced founders and CEOs. We are here for the next Hassabis, to try to meet their ambition.

This brings us back to the story of DeepMind, which in 2014 was acquired by Google for just £400m only four years after launching. Hasabis now runs the entirety of Google’s AI efforts from London and has delivered breakthrough after breakthrough, from AlphaGo to AlphaFold. I first wrote about the cost to the UK of DeepMind being acquired back in 2018 in an essay “AI Nationalism”, but in 2024 this seems even more stark.

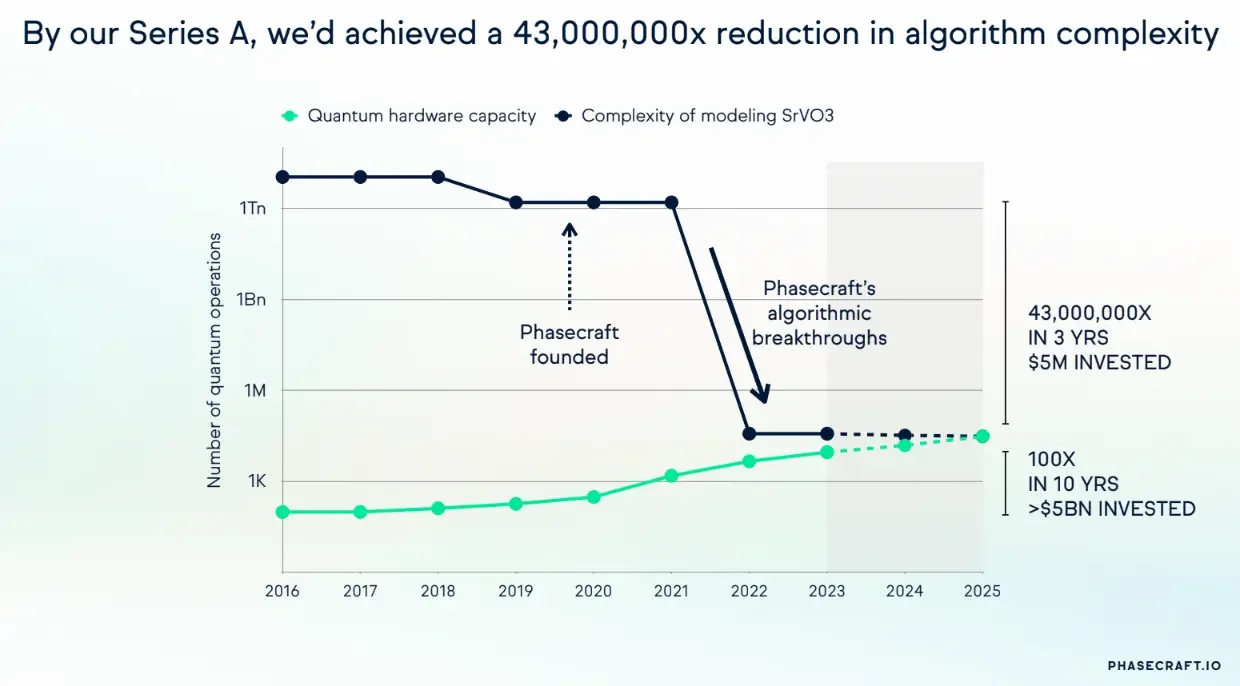

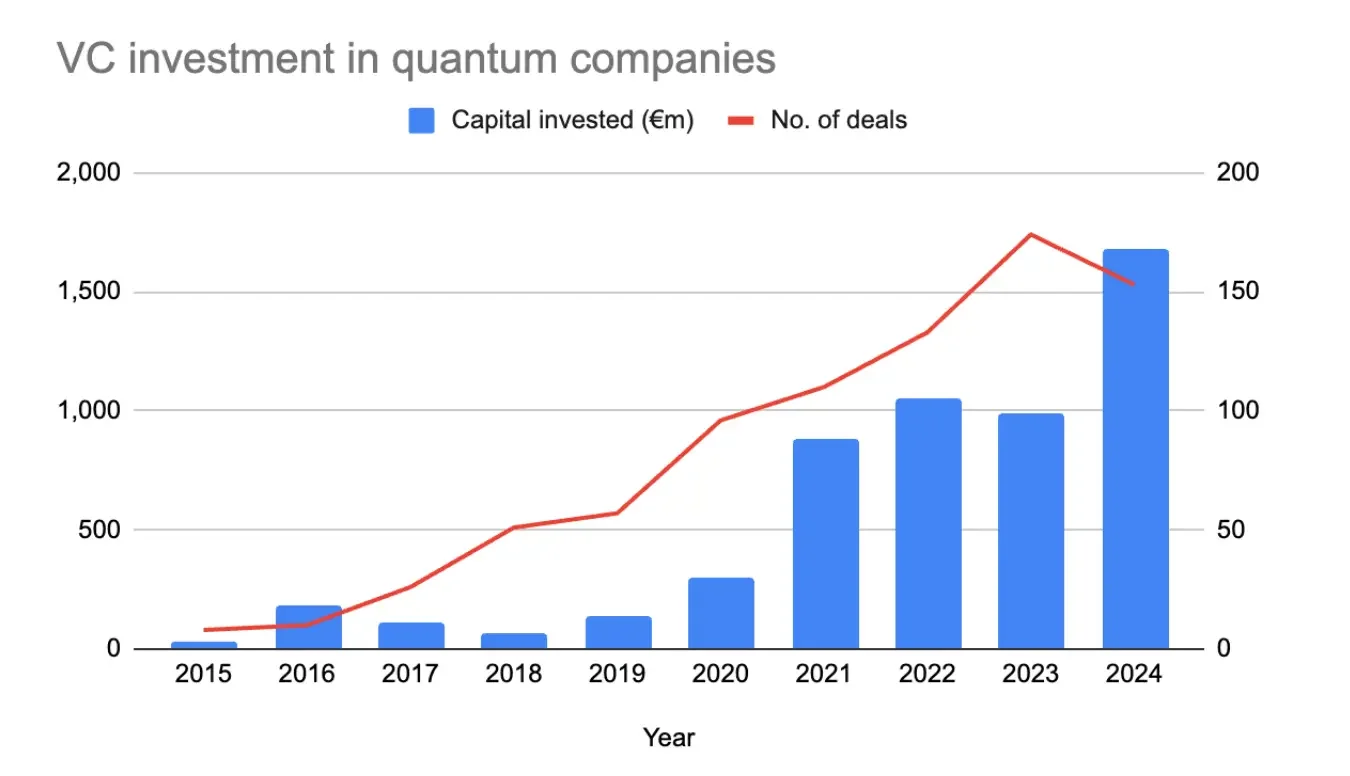

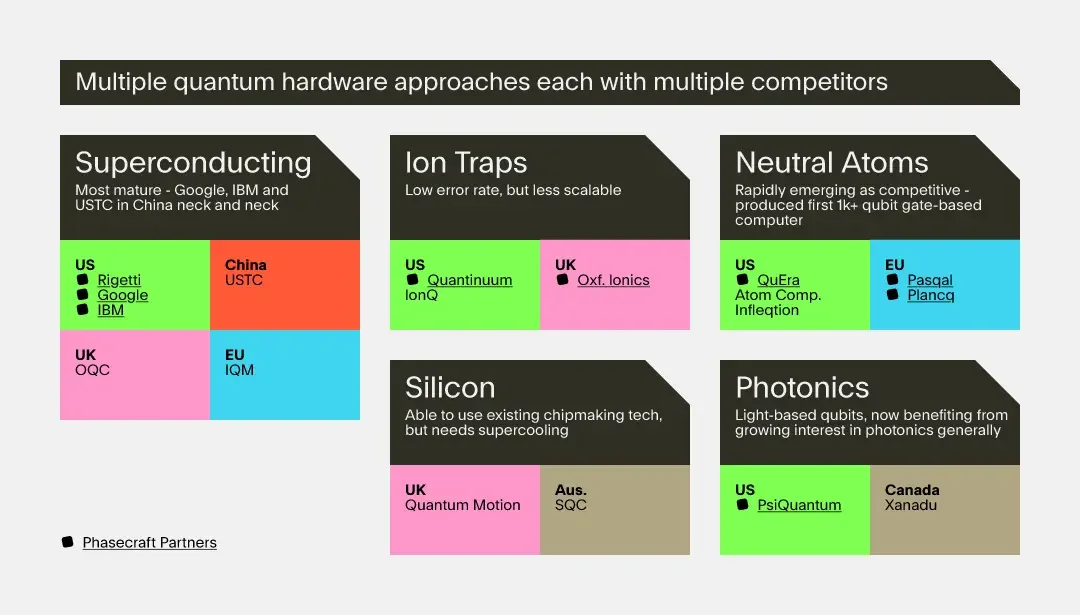

What happened? I would argue that there was simply not enough audacious capital available for Hassabis to pursue his mission and instead an experienced founder - Larry Page with all the resources of Google - was able to provide the billions in long-term high-risk funding that he needed. The same is true in self-driving cars or quantum computing, where Google has invested billions in technology that could take a decade before it makes money. Consider how different things could be today if someone in Europe had the audacity to be a true partner to Hassabis and funded him to stay independent.

Meanwhile in Silicon Valley, a group of experienced founders, most notably Sam Altman and Musk, were thinking hard about how important AI could be and how to compete with DeepMind as they founded OpenAI. In 2015 Altman emailed Musk saying: “Been thinking a lot about whether it’s possible to stop humanity from developing AI. I think the answer is almost definitely not. If it’s going to happen anyway, it seems like it would be good for someone other than Google to do it first”.

Musk then became the largest donor to the new non-profit OpenAI. The goal was very explicitly to catch up with DeepMind. In emails released as part of a court case, Musk wrote to the co-founders in 2016: “Deepmind is causing me extreme mental stress.” and in 2018 “My probability assessment of OpenAI being relevant to DeepMind/Google without a dramatic change in execution and resources is 0 per cent. Not 1 per cent … I wish it were otherwise … Unfortunately, humanity's future is in the hands of [name redacted by lawyers]”.

Fast-forward today and OpenAI is now valued at over $150bn, Anthropic, founded in 2021 by OpenAI alumni, is reportedly valued at $40bn and X.ai, founded by Musk in 2023, is valued at $50bn less than two years after founding. A set of well-resourced founders - Larry Page, Elon Musk and Sam Altman - tilted history and now Silicon Valley, not London, is the global centre of gravity for AI.

Next-generation technology

But, while Europe might have fallen behind in that race, AI is still young and much is yet to be written. And beyond AI, there are potentially world-changing technologies being built in Europe that urgently need bold capital to grow.

One example is nuclear fusion. Fusion could be the ultimate solution for zero-carbon, low-cost, baseload energy. For Europe it could be a source of energy security as well as an opportunity to build a huge new industry. A start-up that builds fusion reactors like SpaceX builds rockets could be the next trillion dollar company.

This should be an area where Europe is positioned to lead - it has invested more public funding in fusion research than the US and has a larger base of fusion scientists. European governments have led the way with the Joint European Torus, the tokamak with the record for fusion power in the UK and the Wendelstein 7-X in Germany, the world’s most advanced stellarator. Europe should be poised to win.

However, when you look at private start-ups in fusion, four in the US have raised over $500m, compared to only one in China and zero in Europe.. And again it comes back to audacious founder-led capital, with the best-funded US fusion start-ups raising their early rounds of funding from Altman, Vinod Khosla or Bill Gates. Experienced founders are the ones able to optimistically embrace these kinds of high-risk projects that define the next branch of the tech tree.

We’re seeing glimpses of how this can work in Europe. In 2021, Prima Materia (an investment company set up by Daniel Ek, founder of Spotify) invested €100m into AI defence startup Helsing when there was no alternative investor standing in the wings - he was the only person willing to take this level of risk. Helsing is an example of a truly innovative European company that has now secured a series of major government military contracts. That early investment substantially de-risked the business, allowing Helsing to raise more than $830m from venture capitalists over the subsequent three years. It was a catalytic event of a kind that doesn’t happen enough in Europe.

Don’t sell

Another reason I call experienced founders a keystone species is that, along with founding and investing in more ambitious start-ups, they also support the next generation of founders in more nuanced ways.

Experienced founders can lend their scar tissue to a new founder and help them avoid the mistakes they made. Consider how Sean Parker, co-founder of Napster, took the experience of being fired from his previous start-up and used it to help Mark Zuckerberg retain full board control of Meta, something that became critical in July 2006 when Yahoo made Facebook an offer to acquire it for $1bn. With complete control of the board, Zuckerberg could choose to reject the offer, despite advice from board members to take the deal. Fast-forward to today and Meta is one of those trillion-dollar US companies.

Ek was a second-time founder when he started Spotify and, despite a reported billion-dollar offer to sell to Google in 2009, remained independent; the company now has a market cap of over $95bn. The obvious point is that to eventually be worth $1tn, you need to not sell earlier for a number smaller than that.

This story illustrates the importance of a mission-focused founder, but not selling can also be due to sheer incompetence from an acquirer. In 1998, Google’s founders tried to sell their company to Yahoo for $1mn, Yahoo refused and they kept building. Later, in 2002, Yahoo realised the value of Google, offered $3bn, Google said they’d sell for $5bn, Yahoo balked again and 22 years later Alphabet is worth more than $2tn and owns DeepMind.

Dutch payments company Adyen didn’t sell and is now worth $50bn, Wise is now worth $12bn and Arm Holdings is the UK’s most valuable technology company, worth $160bn, but only because an attempted acquisition by Nvidia in 2020 was blocked. Can you even imagine the level of dominance Nvidia would have today if it owned Arm too?

Great companies take time. ASML, Europe’s leading technology company, is now worth over $280bn, but has been consistently tackling its mission since 1984. Nvidia is a $3.3tn company today, but in 2010, when it was 17 years old, it was valued at less than $10bn. If Europe wants a true tech giant, it will require steely determination from founders and investors to not sell and keep building.

The Skype story

If you want one solid European example of the cost of selling, you need look no further than what happened with Skype.

It was the tool that made me really fall in love with the raw potential of the internet. Skype felt like the first true global social product and provided free and high quality international calls. It had a level of virality that is rarely ever seen with consumer internet products, scaling from zero to 50m users in just two years. Even today, twenty years later, this would be a remarkable rate of growth!

It had a business model (I paid for it!) and was generating tens of millions in revenue. Skype was bought by eBay barely three years into its life, the founders left, then it was bought again by Microsoft, and rapidly declined inside these gigantic US companies into irrelevance.

What could have been? Skype anticipated so much of what followed in social networking and you can still see its core vision carried forward by WhatsApp — a remarkably Skype-like product — which today has over 2bn users.

The early Skype team was in the language of the kids today, “cracked”. Taavet Hinrikus, the first employee and now my partner at Plural, went on to found Wise. Cofounder and CEO Niklas Zennström went on to found London VC firm Atomico that’s backed companies like Stripe, Klarna and Telegram.

Fellow cofounder Janus Friis, along with Skype chief technical architect Ahti Heinla, launched Estonian robot delivery company Starship Technologies. Other alums include Jaan Tallin, Skype’s founding engineer, who became one of the world’s greatest technology investors having made early bets on companies like Anthropic, DeepMind, and Ethereum. It wasn’t a lack of European talent that held Skype back.

I believe if Skype had not sold and remained independent today, it could have been the first trillion-dollar European tech company - the defining social networking company of today instead of handing that role to Meta. Why did it sell? For the founders and investors, it was hard to turn down the $2.6bn offer in the post-bubble doldrums of 2005.

Moving forward, we need both entrepreneurs and their backers to stand firm behind the ambition of their ideas, and avoid selling more brilliant companies to US rivals before they reach real scale.

Ironing out creases

While Europe’s founders are the most important part of the puzzle, Europe’s policy makers need to show urgency in removing barriers to innovation. Founders here still face friction that a Silicon Valley-based entrepreneur would find simply inexcusable.

An egregious example is the German notary system, a bureaucratic minefield that not only sucks valuable time and hefty legal fees from early-stage founders, but completely disincentives angel investing from outside of the country.

You don’t need to look far on Linkedin for stories like that of Cologne-based AI meeting assistant startup tl;dv, which recently shared how it paid a €40k notary bill, after receiving an €85k investment, all because the round featured an international backer.

High costs and cumbersome rules like this have completely destroyed the angel ecosystem in the country and my bar for investing in German companies has always been higher as a result. When it comes to introducing a German start-up to a Silicon Valley-based angel, I think, “what are they going to do when they learn about the notary shit?”. Angel investors tend to be busy founders who, unlike a VC firm, don’t have a team to take care of this kind of bureaucracy. By putting more hurdles in their way, you’re stalling a vital cog in the machine that helps accelerate ambitious ideas at their earliest stage.

Another obvious problem to solve is the system for spinning out companies from European universities. We have an incredible scientific powerhouse in the continent’s academic sector — with more than 30 of the world’s top universities here, but we are still not good enough at getting that research out into the world and turning it into impactful companies.

A big part of the problem comes from the equity stakes taken by European tech transfer offices, the university institutions that manage the commercialisation of intellectual property that begins life in academic labs.

European universities are known to take stakes as high as 40%, making it almost impossible for outside investors to come in. Oxford is infamous as one of the worst offenders here, with a recent survey by spinout policy research organisation Spinout.fyi showing that the university takes an average equity stake of 27%.

Compare that to Stanford in Silicon Valley, which boasts tech giants like Cisco Systems Hewlett-Packard and Sun Microsystems among its graduates, where the tech transfer office typically asks for between 1-5% equity.

By 2002, Stanford companies were worth more than $530bn on public markets while, by 2021, Oxford spinouts had a combined value of $8.4bn. European universities should ask themselves: “Would I rather have a 5% stake of $500bn, or a 27% stake of $8.4bn” — the maths is not complicated.

Politicians are beginning to take notice: the UK government recently conducted a review of spinout policies to try and improve conditions for commercialising research, but its recommendations still do not go far enough. We need to be even more founder-friendly in European academia and follow the Stanford playbook.

Europe, stand up tall

With these raw ingredients and a promising direction of travel, Europe feels like a potential tinder box of innovation ready to take flame. But we need to keep fanning those flames, and marketing our success stories better.

You only need to compare payments companies Stripe and Adyen — worth $70bn and $50bn respectively. It’s not a massive delta, but I’d guess that far more Europeans have heard of Stripe than the number of Americans that have heard of Adyen.

Belgian nanoelectronics company IMEC is another example. It’s one of the top places in the world where companies like Nvidia and TSMC come to collaborate on cutting edge chips, but hardly anyone knows about it.

Secret success stories like these should stay secret no longer.

And while Europe is yet to produce its first trillion-dollar tech company, that’s not the first aim of the game. To give itself the best chance of creating one of those truly iconic companies, it must create as many $100bn companies like Spotify as possible.

Things need to happen urgently as time is running out to stay in the race and it’s time for Europe to build these remarkable vehicles of scientific progress and economic growth — not only to grow the tech industry, but to power our nations to be more prosperous as a whole. If we do, we could soon be living in a world powered by European-built nuclear fusion power plants or solving some of science’s most complex problems with quantum computers that have been developed in London or Munich.

This isn’t just about growing the tech industry for those that work in it: it’s about creating a more prosperous and resilient society with more wealth to pay for Europe’s public services.

The next branches of the tech tree have the potential to truly benefit humanity and there is no reason they can’t be grown in Europe. Regulation isn’t the core problem - the key is to cherish the role of experienced founders, celebrate when they fund the riskiest and most important tech, stop selling the most precious companies to US acquirers and turn an already powerful innovation engine into a harder-edged ambition to keep scaling in Europe.

It’s time for Europe to stand up tall.